Assessing Your Equine's Overall Fitness

By Terre O’Brennan

Or we may be looking towards our tenth straight month of attending rides and asking ourself, “Does this horse perhaps need some time off?” Or, after years of building a base and months of intense training we are wondering, “Do we dare risk racing for the ‘big win’?”

We have been doing our best to prepare our partners for the job we want them to do — but how can we tell if we have succeeded? We have a number of tools available to help us make this assessment; the first and most important one must always be observation. It does little good to increase your partner’s cardiovascular fitness at the cost of his soundness or his comfort. Most training programs concentrate on heart, lungs, and cooling, but we must never neglect the legs, mind, and overall well-being. Fitness shouldn’t hurt.

Body weight

One excellent way to keep track of your horse’s general condition is to monitor his body weight. Each horse — like each rider — has a body weight at which he feels and performs his best. We would ideally like to keep our partners close to that weight during our competitive season, even if we allow or encourage them to gain weight during a winter layoff. (In northern climes many of us feel our horses spend a more pleasant winter if they have a good layer of fat under all that hair!)

It is a long accepted practice to “feed by eye” — if the horse is losing weight with work, feed a little more; if he isn’t losing his off-season fat fast enough, or is gaining weight on pasture, feed a little less. However, by the time you can see a gain or loss of weight, you may be in the region of 50 or more pounds. This much weight can be difficult to replace during ride season, or to take off a horse on pasture.

It is therefore a very good idea to actually measure the diameter of your horse’s body periodically. Use a weight tape or a standard tape measure at the girth area (just behind the withers) and record the measurement. Changes will indicate a gain or loss of weight much sooner than the naked eye will see them.

Cardiovascular fitness

Our biggest concern, however, is cardiovascular fitness — have we prepared our partner adequately for the job we have planned for him? We are conditioning regularly, but is it enough? We know he comes back to his former level of fitness fairly quickly after a layoff — but is he there yet? It is possible, and not particularly difficult, to actually measure the effects of your conditioning program. Improved fitness is the result of adaptation to stress; researchers measure this using treadmills and monitoring pulses during precisely defined workouts. This is obviously not practical for the average endurance rider! There is, however, a simple and effective way for us to do the same thing: we can measure cardiac recovery.

Essentially, we need to standardize a workout, and keep track of how rapidly our partner recovers from it. Here is a formula given to me by Gayle Ecker of the University of Guelph (you will need a stethoscope and stopwatch or heart rate monitor):

Measure off a known distance that will remain fairly constant in footing from one repetition to another. ~A five-mile section of trail, a one-mile gravel road up a gradual slope, a five-mile distance around a series of fields. ~Use an ATV, dirt bike, or vehicle to measure off the mileage (or kilometers).

After a warm-up of 15 to 20 minutes that includes walking, trotting, a bit of cantering, until the body temperature of the horse is warm, start the fitness test. ~Trot your horse over the distance and, using the stopwatch, time your duration over the chosen trail. ~ You can trot some, canter some, even walk some, according to the fitness level of the horse. ~The overall intensity/duration should not be harder than your general training miles. ~At the end of the distance, record the time in a little notebook that you carry in a pocket.

Start the watch again at the stop of exercise. At two minutes, take the heart rate using the stethoscope for 15 seconds. Record this number. ~While dismounted, walk the horse along and re-take the heart rate for 15 seconds at five minutes, 10 minutes and 15 minutes. ~Record these numbers. ~Cool out your horse (or continue with training miles, depending on the fitness level and your targets for training).

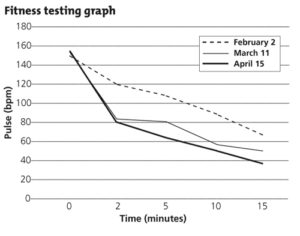

Once back in the barn, construct a graph (you can purchase graph paper from a stationery store to make this easier). Along the bottom of the graph (the x-axis), put the time (0 to 15 minutes). ~On the upright axis (the y-axis), place heart rate.

Record the heart rates above the appropriate time (HR at two minutes, five, etc.). ~Connect the dots. ~Note the slope of the line. ~Repeat the same test, keeping the distance/duration as much the same as before. If you start this now, and repeat it in the spring, you will have an objective measurement of how much conditioning has been lost over the winter, and then you can track the fitness gains over the season next year.

As an example, I often ride in a park with a seven-mile-long trail. When I do this fitness test, I warm up for two miles — walking, jogging, tightening my girth, etc. At a set landmark I start my stopwatch and ride the next five miles in as close to one hour as I can manage. I use that rather slow pace (5 mph) because it is one I can achieve even in bad footing, early in the year. Later, when the horse is fitter and the footing is drier I can ride faster, but take more breaks to end up with the same speed.

This course ends with a mile-long hill — steep at the beginning and then more moderate. I make sure I trot or canter from the bottom of this hill to the top — and that’s where my five miles ends. I should have a near-anaerobic heart rate at that point. I can then dismount and walk downhill to my trailer while taking the pulse at two, five, 10 and 15 minutes. I can then graph the recovery.

Note that the rate of recovery is pretty much independent of how high the initial pulse was — this can vary with temperature or excitement. As the horse gains fitness, the slope of the line should become steeper, i.e., recovery improves. If it does not, I am not accomplishing much in the way of improvement.

If it actually became shallower — indicating recovery was worsening — I would know this was a red alert; either I was training too hard and the horse was unable to adapt to the workload, or I had a lameness or illness brewing below the surface. Time to back off!

The graph shows a steady improvement in fitness between February and April — not only are the pulses lower, but the slope of the line is steeper. If you begin this testing at the start of the new season with a record of your partner’s past recovery rate, you can more accurately judge how quickly he is regaining his former fitness.

Attitude

The final method of assessing the effects of our conditioning program is difficult to quantitate, but is perhaps the most important of all — weighing our partner’s attitude. Endurance horses love their work (perhaps a little too much, in some cases!).

If we see them become sour, unwilling to be caught or reluctant to load, we need to question our program. There is no sight more beautiful than a fit, happy horse doing work he enjoys — this should be our ultimate goal.